What did ancient Indus people eat? What kind of crops did they grow? What did they cook? How might these things differ by city, town and region? To even get close to answering these questions, one needs a "a systematic collation of all primary published macrobotanical data, regardless of their designation as ‘crop’, ‘fully domesticated’ or ‘wild/weedy’ species," writes author Jennifer Bates. As part of her Ph.D thesis, she collated all this information scattered through published excavation reports and articles. She describes and explains her approach in the paper, and then links to the open data set she prepared (in .csv files). In the process, she manages to fix misspellings and other ambiguities across decades of discoveries by archaeologists from countless nations. The result is the basis for much deeper and more meaningful research in the years to come given the time-savings that ensue for future researchers who had a ready place to look-up (and add) data.

One of the best things about archaeobotanical data is that it is subject to discovery, whether through fine mesh straining at sites that yield, say, seeds and other residues which can be subject to increasingly less expensive radiocarbon dating and other investigations that trace remnants of oils and spices and even their combinations in cooking pots and other vessels that are key to building a picture of ancient Indus "foodways" as experts like to call "the eating habits and culinary practices of a people, region, or historical period." An enormously valuable infrastructural contribution by a young scholar likely to make important contributions given this methodical approach.

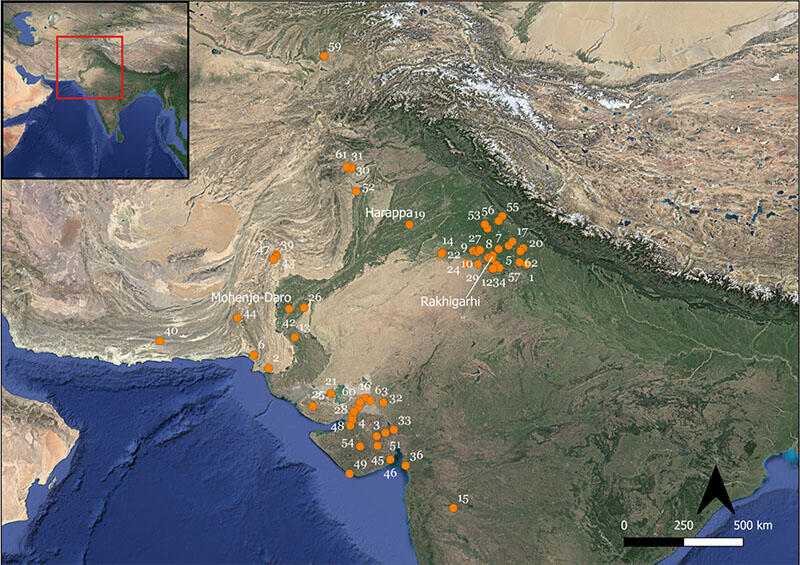

Above: Map of Indus sites with archaeobotanical data. Numbers correspond to site names, found in file “ICArchbotSites.csv” deposited in the online repository.

- Log in to post comments