An important paper - given the painstaking analysis of data - which shows just how careful one has to be in attributing the demise of the Indus civilization to climate change. "A thorough accounting of how Indus peoples were impacted by—and may have adapted to—climatic fluctuations at the end of the third millennium BC requires investigation of the specific ways in which local populations engaged with their environments and how land-use patterns changed during this period of social and climatic change (Madella and Fuller, 2006; Petrie, 2017; Petrie et al., 2017; Wright, 2010, pp. 39–44)," write the authors (p. 1). They look at pastoral practices at three sites Gujarat - Bagasra, Shikarpur and Jaidak – before and after the roughly 2000 BCE climate change event, when a major shift in the summer monsoon is thought by some to have led to major societal transformations on the ground. Given that the land became more arid, would pastoral peoples not have roamed more widely to feed their livestock? "Together, data from these three sites allow us to determine the extent to which pastoral land-use practices changed across the period when climatic changes may have impacted local environments" (p. 2).

They sort through the complexities of Bronze Age Gujarat - Indus civilization seems to have co-existed with other traditions before and afterwards - and the types of animals eaten (mainly bovines and caprines, or cows and buffaloes, sheep and goats) in what they call a "bottom-up epistemological approach" (p. 4). To put it simply, assuming that there was less rainfall, pastoral people would have had to range over larger territory to feed their livestock. If they did this, the dental remains of their livestock would reveal greater variety over time. "We evaluate this hypothesis with faunal and isotopic data that speak directly to livestock consumption, management, diet, and mobility at three well-dated archaeological sites whose occupational sequences span the period when migratory pastoralism is proposed to have in- creased. All three of these sites, Bagasra, Shikarpur, and Jaidak, were excavated by the same team of archaeologists from the Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda following similar excavation and documentation protocols. Situated within 65 km of one another, they were located in a generally similar climatic setting. All three have produced radiocarbon dates (Fig. 2, Table 1) that are stratigraphically consistent and commensurate with current understandings of local ceramic sequences. Fauna from all three sites have been studied following the same documentation system (Chase, 2014, 2010), and isotopes in faunal tooth enamel have been analyzed following a common set of procedures developed during the course of pilot studies undertaken in preparation for the current expanded study (Chase et al., 2018, 2014b), as described in more detail below" (p. 5).

The results? After exhaustive dental and other analyses, they write "overall, there is very little evidence for change through time in overall patterns of mobility for either bovines or caprines . . .. In sum, our data show very little evidence for a shift in pastoral land-use practices across the time when climatic changes have been documented in adjacent areas and may have impacted environments in Gujarat. Rather, pastoral land-use practices appear to have been remarkably resilient in the face of the social and climatic changes that characterized the beginning of the Localization Era—as was the case with rural lifeways in other regions of the Indus Civilization (Petrie, 2017, p. 56, 2019, p. 127; 2017, p. 19)" (p. 16).

As other scholars have pointed out as well, Indus peoples were remarkably resilient, and developed infrastructure and practices in different areas that responded to very different agricultural, water, crop and geographical realities. They could adapt. While this does not deny the fact that climate change may have played a major role in the civilization's demise or changes, it is not a simple matter to understand how these effects played themselves out in time. This paper offers a nice way of bringing together the many factors that are needed to develop sharp and effective analyses instead of jumping to simplistic theories.

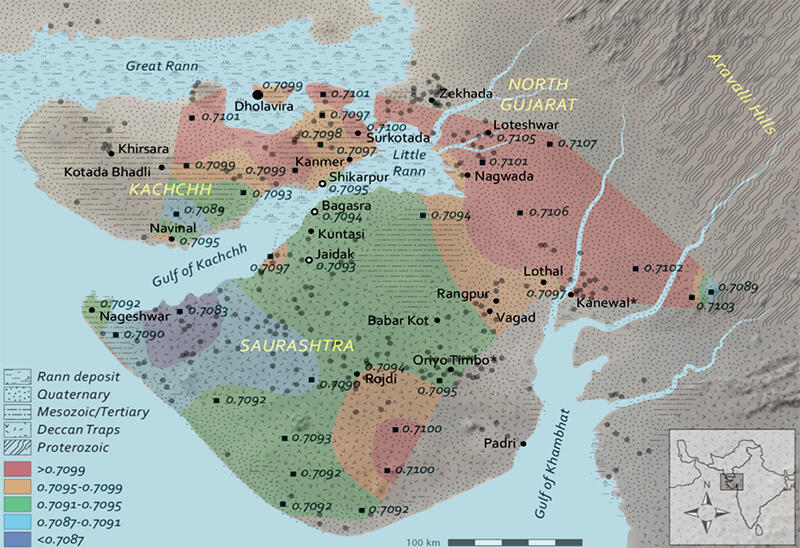

Image: A map of Gujarat showing sites mentioned in the text along with 87Sr/86Sr values monitored in herbivore dung across Gujarat. Black squares indicate dung sampling locations, white circles indicate the sites under consideration here, black circles indicate sites mentioned in the text, and grey circles indicate sites generally contemporary with the occupations of Bagasra, Shikarpur, and Jaidak.