An excellent recent (2019) summary of what we know about ancient Indus foods that were, likely and speculatively, derived from plant resources, and what implications these diverse discoveries over the years have for our understanding of ancient Indus society. "There is a long tradition of Indus archaeobotany," writes Bates, and "this rich archaeobotanical tradition has resulted in a wide array of data and discussions of the roles of plants in the Indus Civilisation, with their use in environmental reconstruction" (p. 879). Some 260 species of fruits, grains and vegetables have been reported, even though many are single scattered finds, and the nature and provenance of these discoveries has varied greatly over the years and many expeditions that have contributed to a large database the author has meticulously assembled elsewhere (see The Published Archaeobotanical Data from the Indus Civilisation, South Asia, c. 3200–1500 BC). While a comprehensive picture of ancient Indus "foodways" remains to be sketched, the evidence is growing that Indus people's enjoyed a rich, varied diet, possibly at least in some areas of well-spiced foods, and if South Asia in recent millennia is any guide, the diets and specific food intake habits played an important role in the (shifting) configuration of society, class and culture.

Bates, like other authorities, divides finds into Tier 1 plants – probably key sources of nourishments like wheat, barley and millets – to Tier II crops like peas, lentils and fruits like jujube, also cultivated but of lesser importance, and Tier III fruits with less evidence and perhaps more regional roles, but still of interest like melons or bananas. She notes how evidence for fruits, which are not cooked, is often much harder to come by because there is no charred residue to survive, although starch analysis is changing that. There is also the problem of wild seeds whose discovery may not indicate cultivation, and the "utilitarian fallacy," that just because evidence of a plant stuff is found, its uses might be presumed and generate wild hypothesis. For example, the slight discovery of cannabis sativa (marijuana) and ephedra (a stimulant) has given rise to speculation about medicinal properties and later usages in texts that are not (yet) well-founded. How too do we interpret dental evidence that cattle consumed ginger and turmeric - was it from eating human scraps, or were they deliberately fed foods containing them (as in Famana)? Different sifting methods at different sites also complicate a holistic picture, as does the accidental ways certain foodstuffs like garlic cloves seem to have been preserved in at least two sites, but not others.

Nonetheless, a picture is emerging, even if a bit blurry, as scientists grope towards a "holistic Indus archaeobotany." It seems as if "spices, flavourings and additions to the staple cereals and pulses were not rare or unusual but a regular part of the Indus diet." (p. 883). Cultural habits like "the frontier between culinary styles existed, between grinding/bread technologies to the west and sticky/boiling technologies to the east" (Fuller and Rowlands, quoted p. 883) may have led residents of ancient Harappa to not eat much rice. She quotes another scholar: "The slow adoption of rice may have been linked to a social re- sistance to this crop, tastes or ideas of social identity, or indicate that rice was a restricted and controlled food, its consumption linked with social class or identities" (Madella, quoted p. 883).

In short, a comprehensive, detailed review of what we know thus far about the fascinating field of ancient Indus nourishment through plants and vegetables, an area where it seems that striking consistencies with the present may well one day be further illuminated by continuing discoveries and advanced sampling and analytical tools not available to earlier archaeologists.

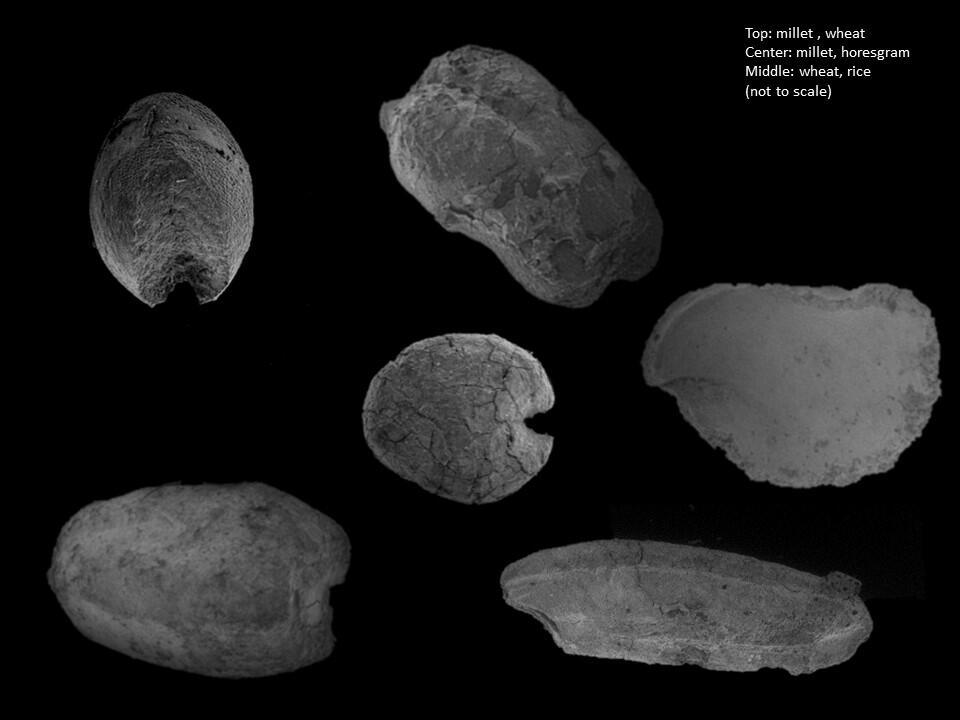

Image: Top: millet, wheat. Center: millet, horsegram. MIddle: wheat, rice (not to scale). Photograph by J. Bates

- Log in to post comments