Perspectives from the Indus: Contexts of interaction in the Late Harappan/Post-Urban period

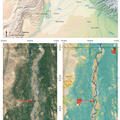

Rita P. Wright, an archaeologist with long experience understanding the Indus areas around Harappa (see the Beas Settlement and Land Survey) looks at the complex evidence surrounding the decline of Indus civilization at the end of the third and beginning of the second millennium (around 2000 BCE and afterwards).