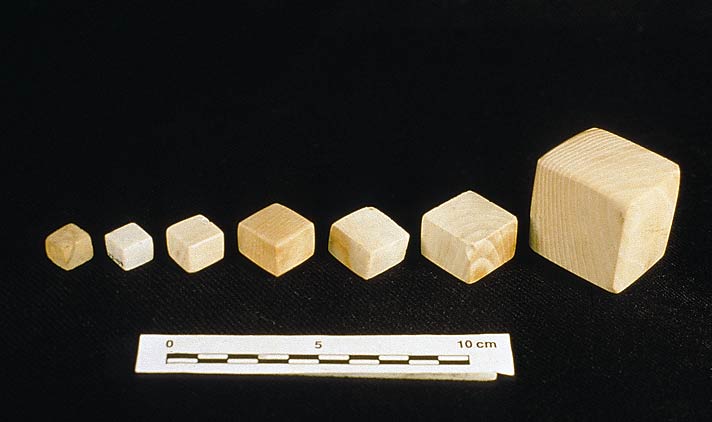

Cubical chert weights from Allahdino, Sindh.

How did they "pay"? I have often wondered how this took place in practice, assuming there was no currency as we understand it. How were luxury / prestige items such as gold and gemstone jewelery obtained by those who had access to them. How did ordinary people trade and obtain necessities and adornments, eg pots, cloth, food, bangles and everyday jewelery? What was the role of the rulers?

How and why (e.g. regulated?) were the (universal) Indus Weights system kept so absolutely accurate? Was there a keeper of the supreme weight? Submitted by Gharial Abramnova from school student questions

Richard Meadow

The concept of some kind of standards certainly existed as there are Indus cubical stone weights, which fall more or less within groups that have relationships with one another and have been called "standardized. There also may have been standards of linear measure as well and also of proportion, although as even was the case until quite recently, these tended to change somewhat through time and vary across space. One can expect that the Indus people had concepts of relative value and these formed the basis for trade and exchange, although what might be valuable for one group might not be for another. For example, lapis lazuli was highly valued in Mesopotamia, but possibly much less so in the Indus (to judge by the paucity of finds), which, however, was much closer to the source in Afghanistan. The Indus people used gold and silver and semi-precious stones and worked large amounts of copper. There is a particularly interesting set of similarly decorated beads that would seem, at least to us, to be of different values. All being red/orange with white decoration, they range from natural stone "eye beads", though carefully shaped carnelian beads etched in white, through beads made of finely ground and high fired hand-shaped silica powder (ground sand) that produced the red and white after firing, to similarly hand-shaped clay beads. The rarest are the natural eye beads, the easiest to produce the clay beads. Items like these, produced by craftsmen, could have been exchanged for other items that those particular craftsmen needed for subsistence such as grain, animal products, pottery, metal tools, etc. Whether this was purely a type of informal exchange system or involved a more structured organization or even something more like a modern bazaar is difficult to tell based on present evidence. As far as rulers are concerned, there is no good evidence for them in the Indus Civilization, which is what makes that cultural phenomenon different from its contemporaries in other parts of Eurasia. And – as suggested by my wording above – the Indus weight system was not absolute. Each weight class includes significant variability. Many of the weights are very small, and overall would have been used for weighing material under half a kilogram (ca. 1.1 pounds), e.g., precious materials, pigments, faience sand, etc.

Iravatham Mahadevan

The Harappans had no money economy. Like all people in the ancient world, the Harappans too traded through barter or exchange of goods. Excavations have produced a series of excellently made weights from agate or other hard stones. They show that the Harappans could weigh goods in a precise manner. There are several technical writings on this subject you can refer to.

Asko Parpola

I am not the right person to reply to this, but barter in kind of various types must have taken place. Grain has been assumed to be a general "currency", but clearly the accurate small weights point to other kinds of "currency" as well, such as precious stones and metals (on their sources see now especially the doctoral dissertation of Randall Law, to be published shortly).