A recent, 95 scientist, massive DNA study in the most prestigious of academic journals, Science. It shows how migrants into India from the west and north contributed to local DNA. "Earlier work recorded massive population movement from the Eurasian Steppe into Europe early in the third millennium BCE, likely spreading Indo-European languages. We reveal a parallel series of events leading to the spread of Steppe ancestry to South Asia, thereby documenting movements of people that were likely conduits for the spread of Indo-European languages" write the authors in this comprehensive and wide-ranging study which examined the "genome-wide ancient DNA data from 523 individuals spanning the last 8000 years, mostly from Central Asia and northernmost South Asia" (Summary).

The implications of this work are described in Tony Joseph's Early Indians: The Story of Our Ancestors and Where We Came From (2019) and align well with the lingustic work of scholars like Asko Parpola in, for example, The Roots of Hinduism: The Early Aryans and the Indus Civilization (2015) even if some of the latter's dates are approximate and subject to revision (see Parpola's recent article on the Sanauli chariots, for example). The authors summarize their entire paper, which is eminently worth reading in full: "By sequencing 523 ancient humans, we show that the primary source of ancestry in modern South Asians is a prehistoric genetic gradient between people related to early hunter-gatherers of Iran and Southeast Asia. After the Indus Valley Civilization’s decline, its people mixed with individuals in the southeast to form one of the two main ancestral populations of South Asia, whose direct descendants live in southern India. Simultaneously, they mixed with descendants of Steppe pastoralists who, starting around 4000 years ago, spread via Central Asia to form the other main ancestral population. The Steppe ancestry in South Asia has the same profile as that in Bronze Age Eastern Europe, tracking a movement of people that affected both regions and that likely spread the distinctive features shared between Indo-Iranian and Balto-Slavic languages" (p. 1).

Although there were limited examples of Indus peoples studied, "by modeling modern South Asians along with ancient individuals from sites in cultural contact with the Indus Valley Civilization (IVC), we inferred a likely genetic signature for people of the IVC that reached its maturity in northwestern South Asia between 2600 and 1900 BCE. We also examined when Steppe pastoralist–derived ancestry mixed into groups in South Asia, and placed constraints on whether Steppe-related ancestry or Iranian-related ancestry is more plausibly associated with the spread of Indo-European languages in South Asia" (p. 1).

There are a number of interesting sub-findings as well, including that the Bronze-Age BMAC [Bactria–Margiana Archaeological Complex] culture in northern Afghanistan and Central Asia "were not a major source of ancestry for South Asians" (p. 4). Instead "we document a distinctive ancestry profile—~45 to 82% Iranian farmer–related and ~11 to 50% AASI [Ancient Ancient South Asians] (with negligible Anatolian farmer–related admixture)—present at two sites in cultural contact with the Indus Valley Culture (IVC). Combined with our detection of this same ancestry profile (in mixed form) about a millennium later in the post-IVC Swat Valley, this documents an Indus Periphery Cline during the flourishing of the IVC. Ancestors of this group formed by admixture ~5400 to 3700 BCE" (p. 5).

To summarize the most directly South Asian-related points, the authors write (quoted from page 5):

"1. Three ancestry clines that succeeded each other in time in South Asia. We identify a distinctive trio of source populations that fits geographically and temporally diverse South Asians since the Bronze Age: a mixture of AASI, an Indus Periphery Cline group with predominantly Iranian farmer–related ancestry, and Central_Steppe_MLBA. Two-way clines that are well modeled as mixtures of pairs of populations that are themselves formed of these three sources succeeded each other in time: before 2000 BCE, the Indus Periphery Cline had no detectable Steppe ancestry, beginning after 2000 BCE the Steppe Cline, and finally the Modern Indian Cline.

2. The ASI and ANI arose as Indus Periphery Cline people mixed with groups to the north and east. An ancestry gradient of which the Indus Periphery Cline individuals were a part played a pivotal role in the formation of both the two proximal sources of ancestry in South Asia: a minimum of ~55% Indus Periphery Cline ancestry for the ASI and ~70% for the ANI. Today there are groups in South Asia with very similar ancestry to the statistically reconstructed ASI, suggesting that they have essentially direct descendants today. Much of the formation of both the ASI and ANI occurred in the second millennium BCE. Thus, the events that formed both the ASI and ANI overlapped the time of the decline of the IVC.

3. Steppe ancestry in modern South Asians is primarily from males and disproportionately high in Brahmin and Bhumihar groups. Most of the Steppe ancestry in South Asia derives from males, pointing to asymmetric social interaction between descendants of Steppe pastoralists and peoples of the Indus Periphery Cline. Groups that view themselves as being of traditionally priestly status, including Brahmins who are traditional custodians of liturgical texts in the early Indo-European language Sanskrit, tend (with exceptions) to have more Steppe ancestry than expected on the basis of ANI-ASI mixture, providing an independent line of evidence for a Steppe origin for South Asia’s Indo-European languages."

A high-informative and thought-provoking article paper that delineates the vast range of information that can be deduced from the rapidly developing field of genetic data – even if, as always, genes, languages and cultures should not be confused with each other, they obviously are interlinked and related and affect each other in profound ways but are not identical. What is also clear from this paper is also how mixed populations throughout Europe, Central Asia and South Asia actually are. It has been a melting pot for some 10,000 years, and we are just starting to figure out the ingredients and their stories.

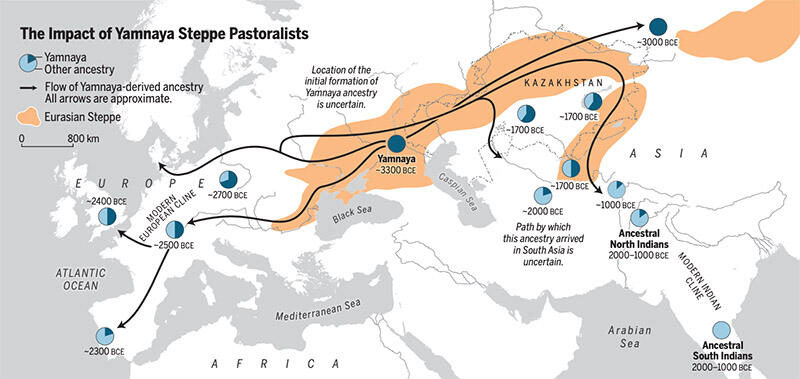

Images: 1. The Bronze Age spread of Yamnaya Steppe pastoralist ancestry into two subcontinents—Europe and South Asia. Pie charts reflect the proportion of Yamnaya ancestry, and dates reflect the earliest available ancient DNA with Yamnaya ancestry in each region. Ancient DNA has not yet been found for the ANI and ASI, so for these the range is inferred statistically.

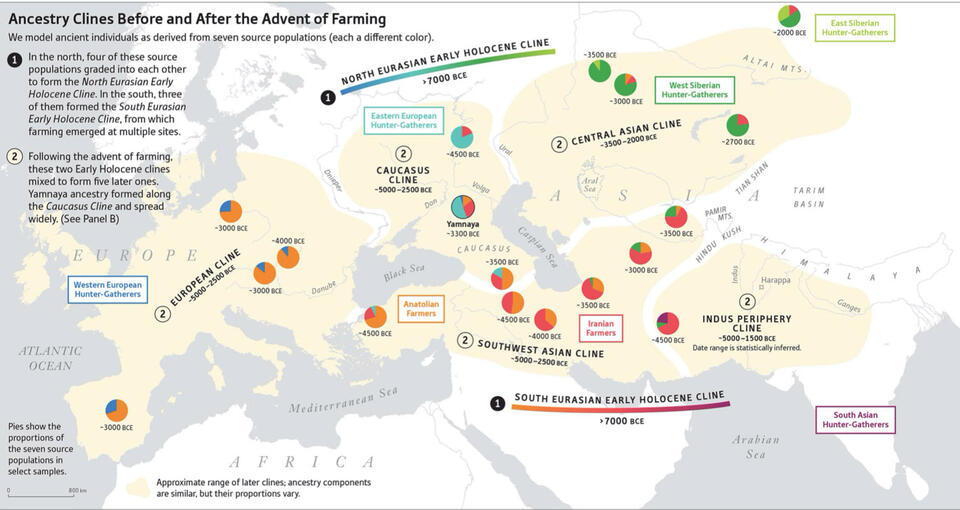

2. Ancestry transformations in Holocene Eurasia. (A) Ancestry clines before and after the advent of farming. We document a South Eurasian Early Holocene Cline of increasing Iranian farmer– and West Siberian hunter-gatherer–related ancestry moving west-to-east from Anatolia to Iran, as well as a North Eurasian Early Holocene Cline of increasing relatedness to East Asians moving west-to-east from Europe to Siberia. Mixtures of peoples along these two clines following the spread of farming formed five later gradients (shaded): moving west-to-east: the European Cline, the Caucasus Cline from which the Yamnaya formed, the Central Asian Cline that characterized much of Central Asia in the Copper and Bronze Ages, the Southwest Asian Cline established by spreads of farmers in multiple directions from several loci of domestication, and the Indus Periphery Cline.