This Indus Seal was found between 1927 and 1931 during the initial excavations at Mohenjo-daro, an Indus Valley site in Sindh province, modern Pakistan.

It was discovered by the British archaeologist Ernest Mackay. From the level that it was found, it was dated to roughly 2000 B.C.E., or the mature urban phase of the Harappan culture.

The area where it was unearthed suggests that it might have belonged to some rich person. Mackay thought its owner was a custodian or controller of a nearby large building.

Application

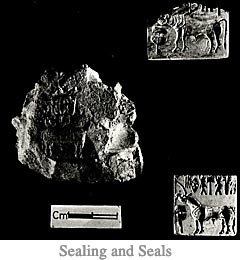

Seals were used for both internal and external trade. A number of Indus seals have been found in ancient Mesopotamia. Impressions of seals ("sealings") were made on ceramics and "tags" used to seal bundles of trade goods. The impression might have been applied to denote ownership or for security.

Seals were used for both internal and external trade. A number of Indus seals have been found in ancient Mesopotamia. Impressions of seals ("sealings") were made on ceramics and "tags" used to seal bundles of trade goods. The impression might have been applied to denote ownership or for security.

Materials and Manufacture

The square shape of the seal is the most common form of Harappan seals, although there is great variety in their size and shapes. The perforation in back is for a cord that passed through the center of the handle (or boss).

Centered and equal to a third of the area on the seal's back, it runs in the direction of the animal, so when suspended, the representation of the animal is properly oriented.

The usual material for Harappan seals was steatite, a soft stone. Steatite seals and boss were cut into shape by means of a saw from one stone.

The boss was rounded with a knife and finished with an abrasive. A hole was then bored to take a cord. Because the boss was liable to be knocked off, the hole was partly drilled into the seal stone to provide more support.

After the inscription was carved into the front of the seal, it was fired, making it extremely hard. Various glazes were also applied throughout the manufacturing process.