Historical Scholarship

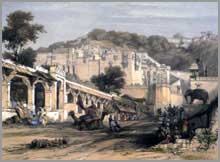

Of the archaeological work that was undertaken during much of the nineteenth century, one was a survey of the ‘Hindu’ and ‘Mohammedan’ monuments, an activity pioneered as a scholarly pursuit by James Fergusson, who ventured out of his lucrative indigo plantation at a rather opportune moment (when indigo prices fell partly as a consequence of the depression of 1830-3) to branch off into establishing an architectural history for British India through a ‘grand tour’, which he undertook between 1837 and 1839. Fergusson subsequently published this tour as Picturesque Illustrations of Ancient Architecture in Hindostan (Figures 5 & 6) on his return to London, and made his aims rather clear. Architecture was to show who the real people of India were, or as he said “what was their former civilisation, and at what point … they may again attain … their former religion, and consequently, how far the present one may be purged of its absurdities––who, in short, are the people we have undertaken to govern, and how, we ought to set about our important duty” (1848, p. 2). On the basis of this one field survey, Fergusson was to champion his authority as the pioneering architectural historian of India (see also Guha Thakurta 2003, and 2004, Chapter I).

Of the archaeological work that was undertaken during much of the nineteenth century, one was a survey of the ‘Hindu’ and ‘Mohammedan’ monuments, an activity pioneered as a scholarly pursuit by James Fergusson, who ventured out of his lucrative indigo plantation at a rather opportune moment (when indigo prices fell partly as a consequence of the depression of 1830-3) to branch off into establishing an architectural history for British India through a ‘grand tour’, which he undertook between 1837 and 1839. Fergusson subsequently published this tour as Picturesque Illustrations of Ancient Architecture in Hindostan (Figures 5 & 6) on his return to London, and made his aims rather clear. Architecture was to show who the real people of India were, or as he said “what was their former civilisation, and at what point … they may again attain … their former religion, and consequently, how far the present one may be purged of its absurdities––who, in short, are the people we have undertaken to govern, and how, we ought to set about our important duty” (1848, p. 2). On the basis of this one field survey, Fergusson was to champion his authority as the pioneering architectural historian of India (see also Guha Thakurta 2003, and 2004, Chapter I).

The other parallel development in archaeological work was the exploration  and identification of ancient ruins and antiquities––an activity,which by the beginning of the nineteenth century had begun to be increasingly undertaken by many travelers, officers of the East India Company, and mercenary soldiers serving the various princely courts within India. This form of investigation was given a coherent direction from the 1860's onward by Alexander Cunningham, through what is now retrospectively recalled as his “text-aided” field surveys (for details see Singh 2005). Cunningham retired from the army to become the first designated archaeological surveyor of India in December 1861, and chose to make his case for his field surveys rather differently from that made by Fergusson twenty years earlier. As Cunningham emphasized:

and identification of ancient ruins and antiquities––an activity,which by the beginning of the nineteenth century had begun to be increasingly undertaken by many travelers, officers of the East India Company, and mercenary soldiers serving the various princely courts within India. This form of investigation was given a coherent direction from the 1860's onward by Alexander Cunningham, through what is now retrospectively recalled as his “text-aided” field surveys (for details see Singh 2005). Cunningham retired from the army to become the first designated archaeological surveyor of India in December 1861, and chose to make his case for his field surveys rather differently from that made by Fergusson twenty years earlier. As Cunningham emphasized:

“Hitherto the government has been chiefly occupied with the extension and consolidation of empire, but the establishment of the Trignometrical Survey shews that it has not been unmindful of the claims of science. It would redound equally to the honor of the British Government to institute a careful and systematic investigation of all the existing monuments of ancient India” (1871, p. v).