Early Efforts

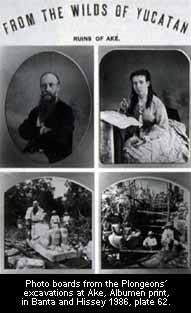

It is in these years that we find some of the earliest efforts of systematic photographing of excavations, one example being the photographs taken by Augustus le Plongeon and his wife, Alice, during their excavations in the Yucatan (Mexico) between 1873 and 1885. The excavators, who were also antiquarians and mystics, had hoped to attain fame and fortune by publishing their photographs, which they took under trying conditions (Figure 3). Instead, they died of abject penury. Forty years later, the role of photography in creating a massive public enthusiasm for the ‘sensational’ archaeological discoveries at Tutankhamen’s tomb is all too evident from The Illustrated London News. Announcing to the readers that “arrangements have been made whereby this journal will publish all the most interesting photographs dealing with Tutankhamen’s tomb, including past and future discoveries”, the ILN also illustrated the ways in which “the click of cameras [had] become as familiar as the creak of the local water wheels” at the site (Figure 4), and reported that “the first special number giving the official photographs [was] out of print immediately after publication” (10 February 1923, p. 194).

At the beginning of the twentieth century, in his Methods and Aims in Archaeology, William Matthews Flinders Petrie, by then a well-known Egyptologist, devoted an entire chapter on how to take ‘correct’ photographs for archaeological purposes.

Petrie’s dictates were rather similar to those of Alfred Cort Haddon, who had five years previously, on the eve of his anthropological expedition to the Torres Strait (Australia), laid down his criteria for photographing for anthropological purposes in Notes and Queries on Anthropology (British Association for the Advancement of Science, 1899, 3rd edition, London).

However, unlike Haddon’s, instructions for ethnographic documentation, Petrie’s injunctions on correct photography for creating archaeological records implicated the making of archaeological evidence, as he reckoned that the latter could only be established through a correct way of seeing.

For Petrie visual memory was an uncomplicated affair, and he was of the opinion that “the master”, or the excavator, “should be able to realize at once, on seeing the place next day, exactly how every one of the fifty different holes looked the day before”

(1904, p. 19).