"The collection was seized on June 11th, 2005 in the customs building of the Karachi sea port. In cases like that, the custom officers fill in a form requesting the examination of the artefacts by a competent authority who will receive this consignment. The museum usually sends the curator in charge, followed in the procedures by a photographer. . .. Subsequently, Mr. F. Arbab took pictures of all the artefacts. After these procedures the authorities decided to confiscate all the antiquities: along with the pottery, a large number of sculptures and wooden artefacts were confiscated and placed in 64 boxes. Later the collection was transferred to the National Museum of Pakistan. . .. The collection represents a very important success for both customs and museum authorities, as such a huge amount of artefacts was never seized before. Moreover, as archaeological excavations have come to a halt in Baluchistan, the opportunity to document previously unknown pottery shapes and motifs is very significant."

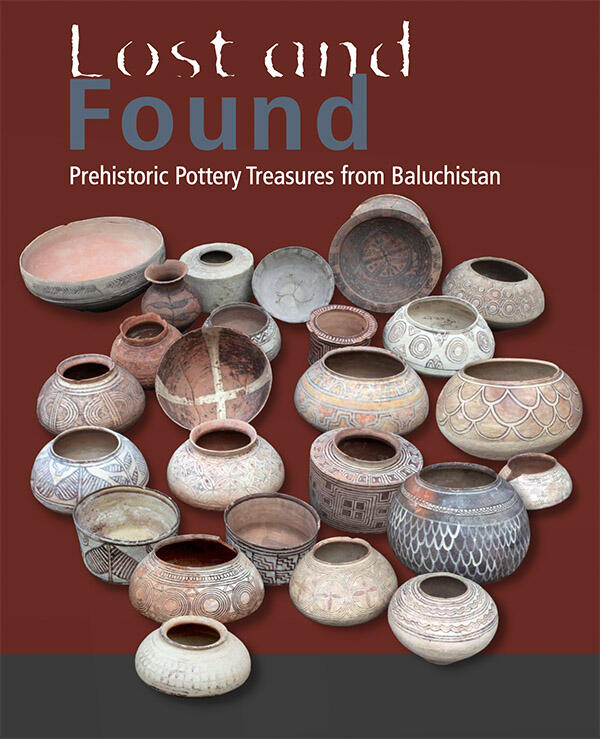

This chilling introduction points to the wholesale looting of ancient history going on throughout the South, Central and Southeast Asian regions today. The situation in Balochistan is especially acute because it is enormous, lightly populated, full of unexcavated mounds, political turmoil, and as this fortunately saved collection shows (64 boxes! how many have gotten through over the years?), home to an incredible array of stunning pottery and objects from long before the ancient Indus civilization. That the collection is available for free as a book (see link below) with superb essays explaining the finds by, among others, Ute Franke and Elisa Cortesi, two Berlin-based archaeologists who have been intimately involved with the excavations that have brought so much of ancient Balochistan to light. It is no exaggeration to say that the book is a real boon for archaeologists and enthusiasts alike, "not intended for specialists only, but also addressed to the general reader. Therefore, introductory chapters with more general contents precede the catalogues" (p. 9). As Vogt puts it: "Over the past 100 years archaeological research has clearly shown that the transition to a fully urban civilization, whose material culture with clearly recognisable markers spread over an enormously large region, was not a sudden event but a gradual process. Its beginnings in Baluchistan can be traced back to the late 8th millennium BCE. Various aspects of this multi-facetted development are outlined in the subsequent chapters of this book, in which a collection of more than 800 prehistoric objects from Baluchistan, confiscated by the custom authorities in the port of Karachi, is presented" (p. 5).

Even just skimming the images remind us of how sophisticated and artistic the various civilizations or cultures that flourished here between the 8th and 3rd millennium BCE were, their enormous emphasis on design and color. Many objects are likely to have been grave goods, and while excavated from smuggler's boxes instead of in situ, so that so much contextual information has been lost, the editors and essayists do an excellent job of reconstituting what they can of the world of these remarkable objects.

As with anything largely written by Ute Franke, it is lucid and pioneering.