January 6th, 2017

Disclaimer: At the time of writing, UTV has removed the official trailer from YouTube. The blog discusses scenes which can be found in the trailers and music videos to limit spoilers.

Context of the Film in Indian Cinema

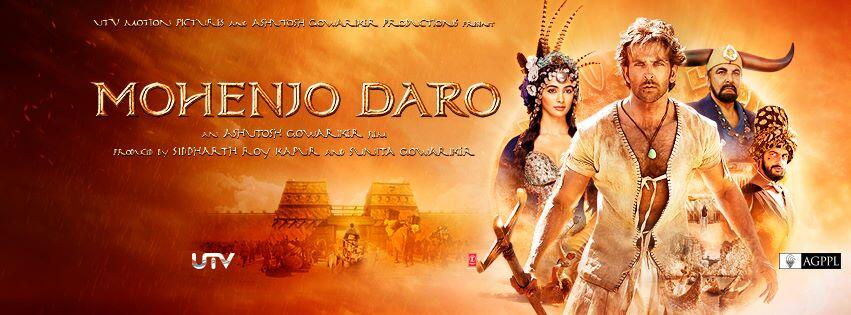

Mohenjo Daro was announced back in 2014 by director and writer Ashutosh Gowariker. It generated a lot of interest because Gowariker had made successful, albeit historically inaccurate, period dramas in the past. These are Academy Award nominated Lagaan: Once Upon a Time in India (2001) and Jodhaa Akbar (2008). It was whilst shooting for Lagaan that Gowariker visited the Harappan period site of Dholavira in Gujarat, India, and was inspired to make a film about the Indus Valley Civilisation. Gowariker consulted many archaeologists whilst researching for the film, including J. Mark Kenoyer.

Mohenjo Daro is unique because it is the first cinematic release featuring this ancient city. In Hollywood and western cinema, there are many dramatisations on ancient Egypt which was contemporary to the Indus Valley Civilisation. In the Indian film industry however, movies do not go earlier than the time of the Buddha or mythological eras. Indeed, the last Hindi language film set in ancient South Asia was probably Asoka back in 2001. Filmmakers therefore seem reluctant in creating stories set in earlier periods, perhaps due to a lack of knowledge about the era or production costs. Asoka was made with a comparatively low budget to more recent historical dramas, yet it effectively captured ancient South Asia and generally followed the key events in the early (or pre-Buddhist) life of the emperor, despite initial criticisms about historical inaccuracies.

Bahubali: The Beginning (2015) has raised the bar in production values and audience expectations, being one of the most expensive and successful Indian films made to date. Even though this is a fantasy film, it is set in an ancient Indian kingdom. This and HBO's Game of Thrones have influenced the way stories are told, especially on Indian television. Hindi language television tends to follow movie trends in that dramas do not go earlier than the time of the Buddha or mythological eras. In recent years, there has been much focus on the Mauryan period (c. 4th century to 2nd century BCE), its first three rulers, Chandragupta, Bindusara and Asoka, and their relations with the Greeks. These dramas follow the storyline of a hero who saves oppressed people from tyrannical leaders whilst getting personal revenge. They also create patriotic and romantic notions of an idealised and unified India that was splintered and needed reuniting against foreign oppressors.

On the other hand, certain types of films can cause controversies and some are banned outright,both within and beyond India's borders, when they deal with contentious history, politics, religion or culturally sensitive topics.

Pak minister says Hrithik Roshan's Mohenjo Daro is a mockery, demands apology: Indian Express

So how does Mohenjo Daro fit in with this context? And why did it create so many controversies?

The Story

Set in 2016 BC, the hero Sarman, played by Hrithik Roshan, is an indigo farmer who travels to the big, bad city of Mohenjo Daro to try his luck at trade and barter. There, he meets the daughter of a priest, Chaani, played by Bollywood debutante Pooja Hegde, and they fall in love. However, she is betrothed to the misogynistic Moonja, played by Arunoday Singh, who is the son of the chief, Maham, played by Kabir Bedi. Sarman must take on these two tyrants who are oppressing the citizens with increased taxes and violence, in order to win the hand of his lady love and free the people. However, a bigger disaster awaits them all. Can Sarman take on this challenge?

The story clearly follows the template of dramatisations on the Mauryans, of Bahubali and of Lagaan, where the hero is saving oppressed people from corrupt leaders and fighting for a higher cause, whilst settling some personal debts.

Lazy Film Making?

The opening sequence in the trailer where the hero floats up a gorge in Central India is reminiscent of the picturisation of Raat ka Nasha from Asoka. These comparisons with earlier historical films are always made because there are certain scenes that are iconic or unique to a particular movie. Sarman then proceeds to battle a crocodile, which was a bit of a joke and not the best way to start the film. Comparisons were also made with action scenes in Jodhaa Akbar which also stars Hrithik Roshan.

The Critiques

Why a Bollywood film has been accused of distorting history: BBC

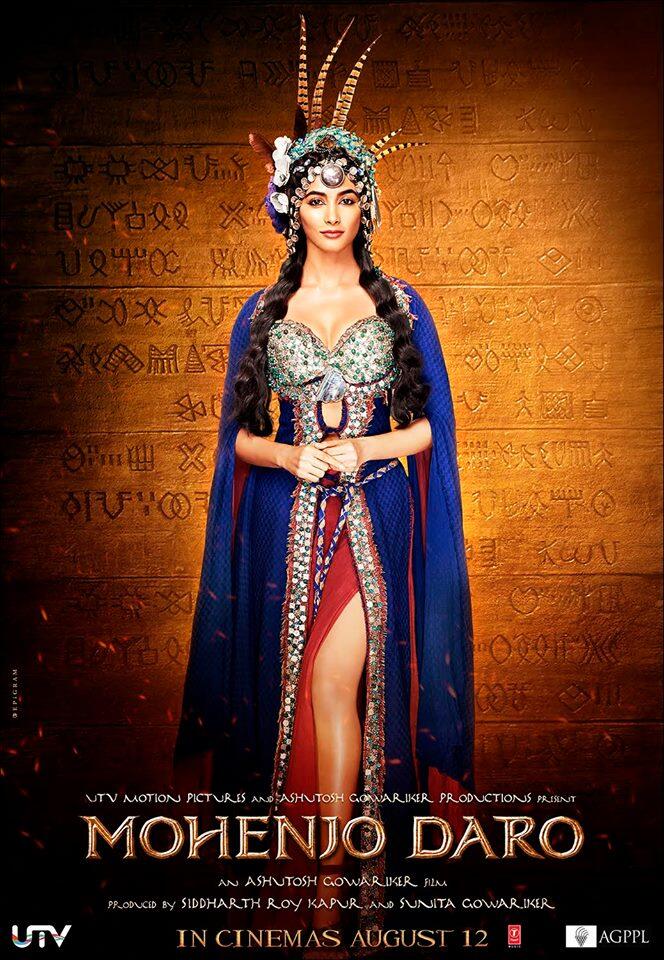

The main critiques of the film were about its perceived historical inaccuracies and the way in which the people were portrayed. They appear to have been influenced by some social media comments made by a history student, who primarily highlighted issues in the costume of Pooja Hegde, which were then picked up by the Indian media. The same outlets which praised the first look of the film were now giving publicity to negative reviews.

Pooja Hegde looks regal in her first look from Mohenjo Daro: IndiaToday

Gowarikar's got it all wrong with Pooja Hegde's Mohenjo Daro poster: Hindustan Times

The poster in Figure 2 was described by the history student as being stereotypical of ancient people and an Orientalist interpretation of the past, where people are depicted in a tribal manner with feathers and paint. Apart from this, there was mention of hieroglyphs being used in the background instead of the Indus script, but this does not appear to be true. The student then wrote a full article and comments beneath it either supported the claims made or called them out for being a distorted view of history. Giving so much attention to social media posts, which are then not independently verified, is dangerous because the media influences how members of the public, who might not have access to the scholarship on the Indus Valley Civilisation, end up viewing the past and how they react to the movie.

To examine the issue further, it is necessary to put the image into context since this was one of the first critiques. It is not clear what the intentions of the filmmaker and the costume department were in choosing to portray an ancient Indus woman in this manner but, through an examination of Indus figurines and images of tribal people in India a few suggestions can be made.

Much Ado About Feathers?

If comparing the headdress of Chaani in Figure 2 to those found on Indus figurines, at first glance it seems odd and not in keeping with the styles depicted. Upon closer examination though, the headdress appears to have been designed by taking into consideration different components of head ornamentations from a variety of figurines, such as the central disc, the shells framing the face, and the use of flowers. The feathers are the only thing out of place. Likewise, liberties were taken in designing an appropriate dress for women, because the Indus figurines are generally nude or semi-nude.

India has many marginalised tribal groups and all have their own cultures and costumes. The people of different states also have their own folk costumes and traditions. Traditional clothing is varied across India as it probably was during the time of Mohenjo Daro. Many have in common the use of head ornamentation, whether this is flowers, feathers, turbans, veils or jewellery. In this regard, it says more about the assumptions of people when they immediately associate feathers with tribal people.

This issue of the feathers therefore has been taken out of context. Initial reactions to the poster suggested that Pooja looks like Cleopatra, or what people imagine Cleopatra to have looked like based on numerous dramatisations of the queen. Overall, the poster is glamorous. It must not be forgotten that this is a movie and the leading lady has to conform to Bollywood standards of beauty. Although Cleopatra the pharaoh is of a later date than the period in which Mohenjo-daro was flourishing, the link to ancient Egypt provides an interesting idea as to why the feathers were used.

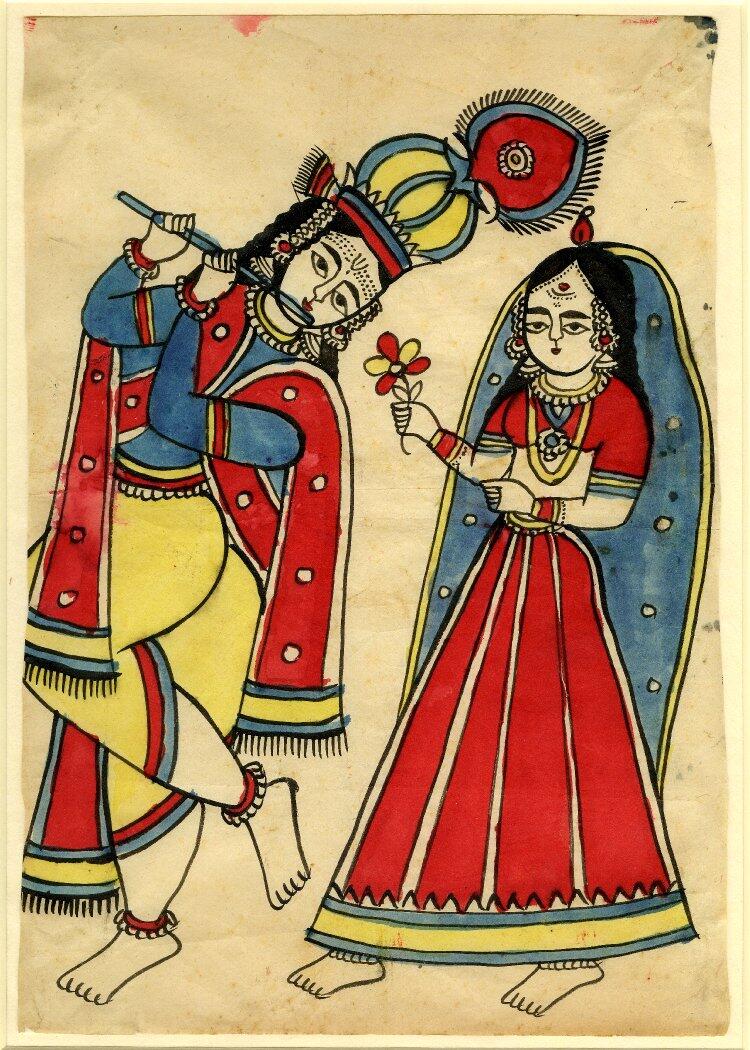

Egyptian deities such as Ma'at and Bes were depicted with feathers in their headdresses. Feathers were thus linked to divinity, as they are in many cultures around the world, and this is not an inappropriate choice for Pooja's costume. Her character, Chaani, is the daughter of a priest and is a living symbol of the river goddess. The headdress then signifies that she is an elite lady with a divine persona. None of the other characters in the film have a feathered headdress. The headdress can be further compared to images of Krishna with a peacock feather in his crown, such as in Figures 3 and 4. The peacock feather is symbolic in multiple ways and is one of the ways in which images of Krishna can be identified.

The headdress can also be compared to those found at the Royal Cemetery of Ur in ancient Sumer (c. 2600 BCE), such as those found in the tomb of Queen Puabi, as in Figure 5. So the costume is trying to evoke an ancient period that was contemporary with ancient Egypt and Sumer, marking out the unique nature of Chaani. Likewise, the use of flowers also marks her out as being linked to the sacred because flowers are offered to deities in India, as in Figures 6, 7 and 8.

Language and Ethnicity

Now to deal with the more contentious issue of race and ethnicity. Particular emphasis was placed on Pooja's skin colour as being too fair to portray supposedly dark Harappans. Many social media comments highlighted that the Harappan people were either Dravidians or Proto-Austroloids, but ignored the fact that Pooja Hegde is of South Indian heritage. It is one issue to question Indian standards of beauty where fair skin is valued over darker complexions, but quite another when ethnicities are attached to past people without the requisite evidence.

Why Has a Naturally Dark Pooja Hegde been made Sparkling White in Mohenjo Daro: ScoopWhoop

Those who were complaining about 'Aryan' actors portraying 'Dravidian' people clearly missed the fact that Pooja speaks Dravidian languages. Language and ethnicity are not mutually exclusive. This is clearly a contentious issue, which can be seen here. The cast of the film is diverse and come from many different states in India. Are any of them eligible to play an Indus Valley person? The cultural and linguistic backgrounds of the actors though have nothing to do with anything because they are playing characters based on a group of people who we still know little about in terms of genetics. Those that complain about such things are denying the participation of Indian actors in what should be accepted as being their wider heritage.

Sarman as a farmer travelling to the city highlights that there was migration of people from different parts of the civilisation, much like modern Indians moving from villages to cities for economic purposes, or travelling further afield. People bring with them their own cultures and ideas, and so Mohenjo-daro was probably a diverse city in that respect at least.

Continuing from this idea that language and ethnicity are somehow linked, social media comments complained about the use of Hindi. Some comments suggested that Tamil would have been a better option. People can request a Tamil director to make a film set in the Indus Valley Civilisation in Tamil and there would not be anything wrong with that, just as there is nothing wrong with making films in regional Indian languages or in English about the ancient Greeks, Egyptians and so forth. But to state that one language should be used exclusively is suggesting that this is the language that the people spoke and it must be used.

Nobody knows what the ancient Egyptian language sounded like, even though its script has been deciphered, but dramatisations will insert a few lines to give the flavour of authenticity. Likewise, Mohenjo Daro opens with a created language, has a mixed (fictional?) Hindi dialect in the dialogues, and the fictional language is used in some of the songs, to acknowledge that, yes, they did not speak Hindi in this civilisation. But this is a film made by the Hindi film industry so the main language will be Hindi for a Hindi-speaking audience.

The script has not been deciphered and, until then, suggestions as to the language are purely hypothetical. This issue, where groups of people feel that they are entitled to particular heritages over others, shows that there is a problem with the education system in India and in other South Asian countries. Instead of advocating a collective heritage, where all can participate, it is divided into religions and peoples, castes and states, and this increases segregation and prejudice. So whose heritage is it? Is heritage defined by national or state boundaries? By language? By perceived ethnicity? Who has the right to Mohenjo-daro?

Diversity or Stereotyping?

The film attempts to celebrate diversity, sometimes in a misguided way, and yet it does perpetuate some common stereotypes found in the west. Traders and merchants arrive from other Indus Valley sites, from Central Asia, Dilmun, Egypt, Sumer and parts of Africa. The title song of Mohenjo Daro illustrates an example of the diversity found in the city. The Egyptians though are shown in Sufi costume and dancing like whirling dervishes. Eastern European or Russian belly dancers, a staple in Bollywood music videos these days, again are used to play Egyptians but they at least are believable compared to the Sufi time-travellers.

In comparison to western films though, Mohenjo Daro at least acknowledges the wider world in which the city flourished. Dramatisations about Egypt, Greece or Rome rarely venture beyond the Mediterranean world, except where Alexander reaches the Indus. There is no mention of South Asia otherwise. The only time South Asian or people of South Asian heritage are present is when they are playing the part of non-Asians, for example Ben Kingsley and Avan Jogia playing the vizier Ay and Tutankhamun respectively in the TV mini-series

Tut (2015). This programme however has a diverse cast, unlike controversial films such as Exodus: Gods and Kings (2014) and Gods of Egypt (2016) which have been accused of white-washing characters.

The portrayal of the Sumerians is stereotypical, where they are supplying weapons (of mass destruction?) to the chief. Whilst the film shows that the Indus Valley people were probably not as peace-loving as has been suggested, it follows Indian ideals about naughty outsiders causing dissension amongst Indian peoples and trying to split them. It also follows trends in American programmes where Middle Eastern people are typically portrayed as terrorists. A prime example is the depiction of the Persians in 300 (2006) as supernatural demons, where the Middle East has been conflated to include Iran. The historical inaccuracies and the portrayal of the Persians sparked an outcry in Iran and by Iranians in the USA.

The graphic novel on which the movie is based illustrates Xerxes as a black man, another racist example of placing black people against white, although in the film he is made a generic brown colour. The story pits the perceived barbarian 'other' against the 'civilised' Europeans in the form of the Spartans. The author recently attended a gallery talk at a museum where the Assyrians were discussed as being barbaric and 'not like us', i.e. not like white Europeans. When Persian or Middle Eastern characters fall on the side of good, they are often played by white actors, as in Prince of Persia (2010) and TV series Tyrant (2014-2016).

This view of non-European cultures by the west is reversed in Mohenjo Daro. The ideal of white female beauty, in the form of the belly dancers, is contrasted with attitudes towards white men. In Mohenjo Daro they appear as two 'Tajik' wrestlers, who are cannibals and are shown as savage, unkempt cavemen. This links back to India's recent colonial past. Ashutosh Gowariker recycles the theme of a simple Indian farmer rising up against the British in Lagaan in multiple ways throughout Mohenjo Daro, whether Sarman is fighting against the corrupt chief (ironically played by a British-Indian mixed race actor) or against the wrestlers. However, the way in which the wrestlers are portrayed is insulting and does not tally with what is known about the Tajiks and about Britain.

The Tajik people occupy areas in modern Tajikistan, Afghanistan and Uzbekistan, which were all a part of the ancient Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex (BMAC), also known as the Oxus Civilisation (c. 2300 to 1700 BCE). Perhaps the wrestlers are the barbaric Aryans which have been brought up frequently in discussions on the film. The BMAC was sedentary and had contacts with the Indus Valley Civilisation. If the 'Tajik' wrestlers are standing in for the British, again Britain was sedentary and Stonehenge had already been constructed. In a way, it is a type of reverse Orientalism and a reaction to the ways in which Indians are depicted in less than flattering ways in Hollywood, such as in Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (1984), a film originally banned in India.

So what about the positives?

Hang on trolls, Hrithik Roshan's Mohenjo Daro is not all wrong historically: Indian Express

Ashutosh Gowariker makes use of key artefacts from Mohenjo-daro and other sites to create his characters and the story. The 'dancing girl' inspired the costumes of the dancers in the title song and makes a guest appearance in a poignant scene.

Pak Lawyer Petitions to get Mohenjodaro's Dancing Girl from India: NDTV

The 'Pashupati seals' inspired the headdress of the chief, Maham. The seals are used in multiple ways, as a token to gain entry to the upper city, indicating a stratified society, and as merchant seals. Trade and barter is represented, something which many Indians have had to resort to recently with the demonetisation of certain currency notes.

The 'unicorn seals' are used to inspire a mythical animal which is symbolic and is the vahana, or vehicle, of the river goddess. The religion is inspired by female figurines that have been interpreted as mother goddesses. The river goddess is worshipped in a cave outside of the city, which takes into consideration the lack of evidence of temples within the city. There isn't anything overtly Vedic in the religious worship. Instead, it appears inspired by yakshi or goddess cults which are associated with many Indian religions, and the priests are modelled more on their Egyptian counterparts than Brahmins.The so-called 'priest-king' statue is given life as the head priest in the film.

The Great Bath, its exact function not known, is envisioned as a ritual bath and can be seen in the song Tu Hai. The reconstruction of the city, beautifully presented in the song Sarsariya, shows the detail that went into creating the set. There is a central square where a time-keeping device is located and market stalls. A wide thoroughfare has side streets where people are engaged in crafts. There are painted pots, figurines, toys and fabric dying. Houses have two-storeys and the city is on different levels. This follows the archaeological findings from excavations.

Musical instruments are featured, including lyres like those from Ur in Figure 9. These are used to inspire the music of the film, by award-winning music director A. R. Rahman. The most evocative music on the album though comes in the form of two instrumental pieces, Whispers of the Mind and Whispers of the Heart, used in a religious capacity.These are the details that make Mohenjo Daro worth watching at least once.

The use of horses and the scene of flooding were also criticised but these are not really big blunders as people have suggested. The four horses are introduced as a novelty item by traders and have no connection to any outdated theories about Aryan invasions. The flood again is not completely out of context. Even if it is archaeologically inaccurate, it can serve to remind people that the archaeological site of Mohenjo-daro is under threat from improper conservation, erosion, groundwater salinity and the looting of artefacts. Hardly any tourists visit and yet it still invokes strong reactions.

Final Thoughts

The story could have done more to connect modern audiences to the past. Issues are brought up in the film, such as the problems farmers have to face in terms of taxes, poor harvests and environmental changes; the attitudes towards the birth of girls and the roles of women, especially significant in Chaani's backstory; corruption and the misuse of power; and population pressure. These are not discussed in any depth and this is where the film failed. There could have been more focus on the daily life of citizens to breathe life into the city and make better use of the set.

However, those who commented positively on the film believed that it was a good way to educate people about the past. Even though it is a fictional story, the physical details of the city are mostly accurate. Where the film raises questions on authenticity, well, even archaeology requires some imagination. For those who do not live in India or Pakistan, where students are likely to learn something about the Indus Valley Civilisation in school (although government sanctioned textbooks often present nationalist ideologies), Mohenjo Daro and other historical films are important in introducing non-Asian or Asian diaspora communities to South Asian history.

When films like Mohenjo Daro appear, they should be appreciated for the thought and effort whilst highlighting issues that can be addressed in future productions. Filmmakers should not be discouraged from making films about the Indus Valley Civilisation after the first attempt. If a filmmaker chooses to use a story based on actual events, it is important to stay faithful to the main ingredients of that story. Likewise, authenticity in settings is necessary when telling fictional stories. However, beyond this filmmakers should be allowed creative licence to make the film that they want to.