March 19th, 2019

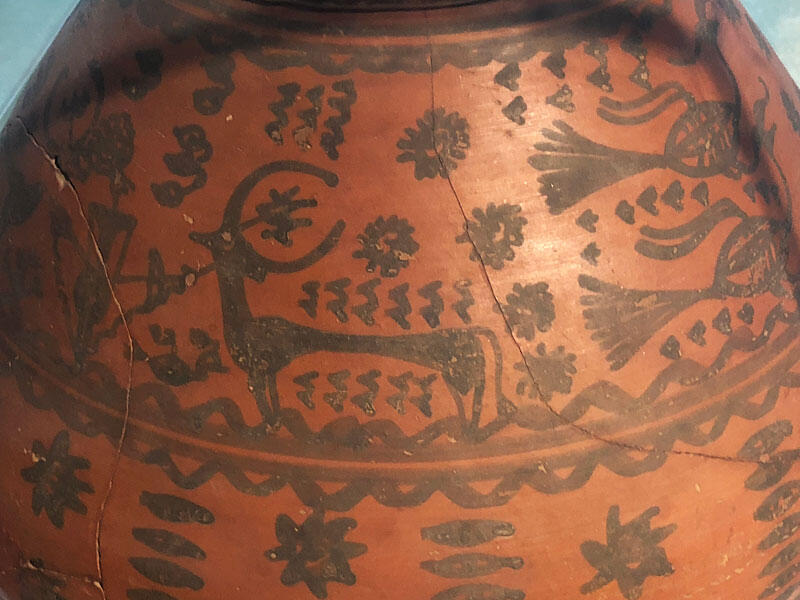

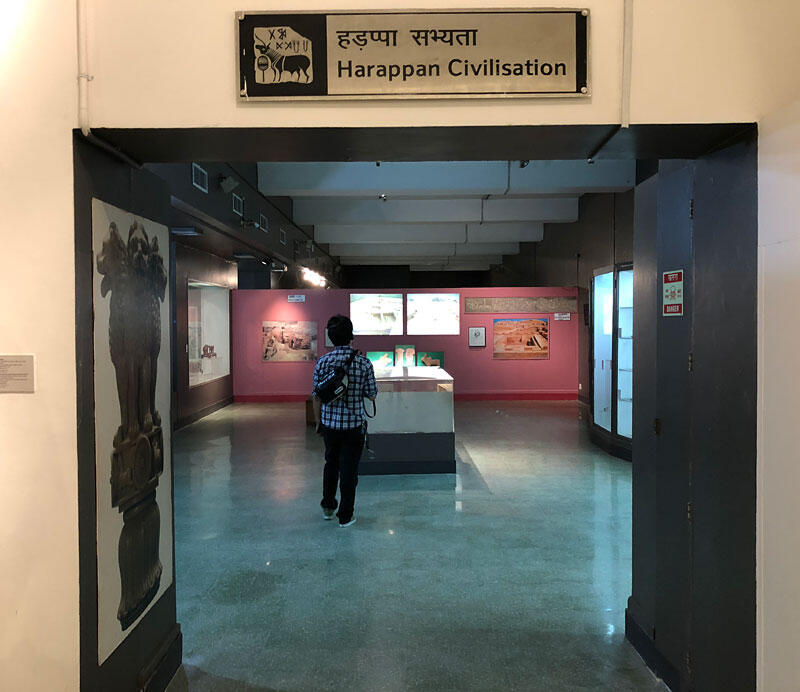

On a recent visit to Delhi, I found myself free for two hours and made my way in a rickshaw from Jama Masjid to the National Museum. It was a Sunday afternoon. After paying the entrance fee and breathlessly arriving at the Harappan Civilisation doorway, I found that it was closed for renovations! Momentarily dispirited, it turned out that there was another entrance and much of the gallery was still open – disaster averted. Fortunately, I was able to glimpse some of the finer Indus objects in the collection, including the wheeled Daimabad bronzes, a painted pot from Cemetery H at Harappa, one of the best-preserved skeletons from Rakigarhi, a surprising mongoose from Dholavira, and of course, a unicorn seal or two.

Most evocative of all, I confronted for the first time one of those headless limestone statues I knew only from black and white photographs. Despite being behind a glass case, I could almost taste its materiality so corrugated was the limestone, like the surface of another planet. There seem to be a number of these headless statutes found at Mohenjo-daro (were the heads lobbed off in some ancient revolt?). Here though it occurred to me that the statue stands in for where we are with respect to ancient Indus studies – so much granular detail, but no face to hold it all together. Thousands of seals, not one sound. Until we can read them, the thoughts that drove the culture are a lingering absence.

The Rakigarhi skeleton had life in it; the Cemetery H pot which once held its own funereal remains offered a vision of plants and animals that must have been wayfarers for the deceased; one could imagine a mound of pilau on the dish-on-stand; and the giant mongoose – where was it going? Why so big? The rhino-on-wheels seemed like it could be at home in a sci-fi movie. I struggled to get a decent photo on my iPhone of the woman riding the chariot of bulls, then gave up. It’s hit and miss in museums, you never know how the lighting or glass case reflections can muddle a shot, but it is always worth trying to find an angle a little different from archaeology texts and papers, in the hope of bringing something different to or out of the object in a real life setting, however constrained. Or it could be its context with other objects that is interesting. Silent yes, invisible no. For all that we have to access Indus images online, there is something different about confronting real objects, in a museum, surrounded by their fellow travelers.

Omar Khan, March 7, 2019