The prehistoric period was certainly the most prosperous period in this cycle: during in the earlier 2nd millennium BCE, the settlements were abandoned and no human traces left, whereas after a short intermezzo during the Historic Period, the sites clearly reflect that away from the cultural, economic, and political centers, migratory pastoralism and a nomadic life-style was the only mode of subsistence and land use.

The earliest site, Adam Buthi, dates to the 4th millennium, but the early 3rd millennium BCE was a period of growth in terms of number and size of settlements. Many sites appear to be associated with dams.

The pattern is very similar during the later 3rd millennium, but then occupation was either restricted to a small area of an earlier site, or sites were newly founded. This late Kulli occupation to which the largest number of sites in southern Balochistan belong, co-existed with the Indus Civilization (Kanri Buthi).

The presence of quite a number of town-like settlements added a new and unexpected dimension to this cultural complex and to an area which so far had remained in the shadow of the Indus Civilization. These new and exciting findings require a rethinking of models of interaction and center-periphery relations between these two areas.

After 1900/1800 BCE the Indus Civilization disintegrated into several regional cultural complexes. In southeastern Balochistan, however, the settlements and irrigation systems were abandoned. No sites dating to the subsequent centuries were found.

The only possible explanations are major population movements or a large-scale and enduring shift in subsistence economy and lifestyle. However, while the transition to a mobile lifestyle is attested to by hundreds of camp sites during the Islamic period, the second millennium BCE is devoid of any human remains.

Likewise, none of the known regions experienced a massive influx of people during that time. On the contrary, areas such as Sindh and Punjab obviously experienced the same development.

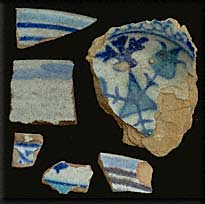

The next traces of settled life date to the so-called Historic Period. However, although some of the Achaemenian and Greek, Mauryan, Kushana, and Sasanian rulers and historians mention southern Balochistan in their records, archaeological correlates for their presence are rare: Settlement types, pottery and small finds are rather unknown and if no coins are at hand, dating is a hazardous undertaking (Hadera Dhan). Diagnostic links to the north, where Pirak and the Swat Valley are well explored and Buddhist sites flourished have yet to be found.

The large number of prehistoric settlements, the size and sophisticated lay-out of some of them came as a surprise: nowadays the area is barren and inhabited by a few people. Interestingly, the sites indicate that a development from village to town and then to camp, and from agriculture to migratory pastoralism took place.

The Islamic Period is marked by a few settlements and fortifications which are located in central areas of Las Bela and Sindh Kohistan or strategic positions in the Hab Valley (13), while no sites other than seasonal camps (14) which are marked by hundreds of "stone benches" and sherd clusters were found In the interior mountain valleys.

These sites date to the 12/13th century CE, the 17/18th cent. and the British Period. The transition to a tribal society, and several conflicts and raids between different tribes and ethnic groups which also caused large-scale migrations were probably major forces behind this development. The Historic and Islamic Period are times of both cultural and economic growth, and of political strength and conflicts.

Many sites in Sindh, Punjab, and the NWFP mirror this development in one way or the other. Both affected the administrative and political centers, among which Bela, Nal-Kaikanan, and Khuzdar are the most important in this region, but not the remote mountain areas which until very recently were the sole domain of migrating tribes and clans.