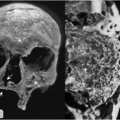

Ancient Skeletal Evidence for Leprosy in India (2000 B.C.)

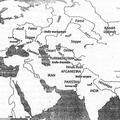

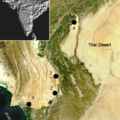

In this article, the authors report on skeletal evidence from 2000 BCE at the site of Balathal, in Rajasthan, India, in an attempt to document the oldest evidence for leprosy.

Balithal has two phases of occupation - a small occupation in the Early Historic period (cal.